Legacy Story: Dr. Fullingim

By Kedrick Nettleton

“Mine was to Stay Here”

A Foundational Professor’s Reluctant Legacy

When Dr. Mike Fullingim retired from his position as a full-time faculty member at Oklahoma Wesleyan University this May, he was one of the longest-tenured professors in the history of the school, leaving behind a strong legacy on campus—and all over the world through the ongoing work of those he taught. The funny part of the story of his career? He never wanted to teach at all.

When Dr. Mike Fullingim retired from his position as a full-time faculty member at Oklahoma Wesleyan University this May, he was one of the longest-tenured professors in the history of the school, leaving behind a strong legacy on campus—and all over the world through the ongoing work of those he taught. The funny part of the story of his career? He never wanted to teach at all.

“Teaching was not on my radar. Missions was what I felt I was called into, and for me that was a lifetime call,” he said.

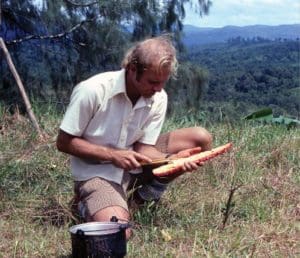

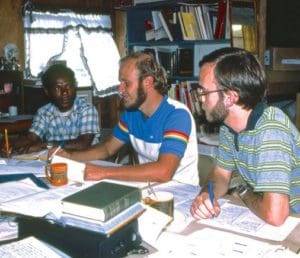

And for almost a decade—eight years total, over an eleven-year period—Fullingim answered that call, working as a linguist and missionary with Global Partners in Papua New Guinea. It was a fertile field, as the country is considered by scholars to be the most linguistically diverse country in the entire world. That’s why Fullingim pursued his graduate studies in linguistics; it was necessary to tackle the country’s complicated wordscape.

“I got a Ph.D., but not to teach,” he said. “I got a Ph.D. to help learn a language better. In Papua New Guinea, there are over 800 languages.”

832, in fact, at least according to the country’s Prime Minister in 2006—and those are languages, not dialects. Linguistic work was a dire need, and Fullingim answered the call.

832, in fact, at least according to the country’s Prime Minister in 2006—and those are languages, not dialects. Linguistic work was a dire need, and Fullingim answered the call.

“I don’t know of one of our missionaries that was fluent in the Wiru language. I don’t know of one of our missionaries that was fluent in Huli,” he said. “So we’re speaking through a second, intermediary language, like Melanesian Pidgin, which is not their heart language.”

The ultimate goal for Fullingim was Bible translation. “I was convinced of the importance of getting God’s Word into people’s language, but that means you better know the language, or at least enough to ask questions,” he said. “Getting my Ph.D. was meant to help me facilitate my work, not to get a teaching job.”

But when Fullingim and his family returned home, and when he finished his degree in 1987, those teaching offers kept coming. Due to his children’s age, it made sense to take a gap year, so Fullingim interviewed and ended up at Bartlesville Wesleyan College—for a one-year contract only.

Eventually, that one year lengthened, and he began as a full-time associate professor in 1989. It was a difficult transition, to say the least, as Fullingim’s heart remained firmly planted in PNG.

“It was kind of challenging to figure out, you know? ‘Lord, send me a postcard and I’ll do what you want me to do,’” he said. “It took me five years to have my stuff returned from Papua New Guinea to here. Five years. I was still wanting to go back. I say we got stuck here, but that was the Lord sticking me here, probably—with me always asking, Lord, is this the year we return?”

A quote from D.L. Moody served to provide a mission statement for this new phase. “He had made the comment that it’s better to train ten people than to do the work of ten people. This is the same work as mission work,” Fullingim said. “There was a message that came to me. You can go back and stay in the jungles again, there’s nothing wrong with that. But somehow, mine was to stay here and train more people.”

And throughout his time at BWC—eventually OKWU—that training has been effective. He’s directly prepared over 200 people to go out into the mission field, a web of global influence that continues to widen with each day, with each convert, in each unique missional context. Alicia is one of those people; she served in a restricted-access field with Global Partners, and her last name is withheld.

And throughout his time at BWC—eventually OKWU—that training has been effective. He’s directly prepared over 200 people to go out into the mission field, a web of global influence that continues to widen with each day, with each convert, in each unique missional context. Alicia is one of those people; she served in a restricted-access field with Global Partners, and her last name is withheld.

“When I realized the Lord was directing me to missions, I immediately landed in several of his classes, and the intro to linguistics course was one of those. Linguistics was an entirely new field of study for me,” she said. “I’ll never forget when Dr. Mike pulled me aside in the dining commons a few weeks into class to talk about my interest and encourage me to pursue it. He believed in me before I believed in myself, and I went on to take every linguistics class he taught.”

Alicia now serves as a missionary trainer herself, indirectly expanding Fullingim’s influence with each person she works with, like ripples in a pond. “The foundation in linguistics gave me a framework for effectively learning language on the field, and helping others on our team to succeed at it as well,” she said.

Even still, Fullingim makes it clear that he had his doubts: “I still say to the Lord, ‘Why did you have me stay?’ I’d never preached a message in Wiru, and I’d gotten to the place where I almost could.”

In the end, it was a matter of trust. “To turn my back on that was really challenging,” he said. “[But] I said, ‘Okay, Lord. I’m still involved in your work.’ I’ll train people, rather than doing the work of ten people.”

The Work Continues

Towards the end of the 2022 school year, Fullingim paused. As he contemplated the next step of his career, he had a chance to look behind and ahead—back on three decades of teaching, and forward to the future of global mission work.

Towards the end of the 2022 school year, Fullingim paused. As he contemplated the next step of his career, he had a chance to look behind and ahead—back on three decades of teaching, and forward to the future of global mission work.

The highlights of his OKWU career are easy to identify: the trips taken with students and the lives won for Christ. Specifically, he points to the numerous journeys taken to establish summer camps in Russia during the 1990s, after the Iron Curtain fell.

“What happened for me in the raising up of many missionaries was the collapse of the Soviet Union,” he said. “We moved into a vacuum caused by communism. That was our fervor here for a while. You could challenge students to go, to teach in youth camps and be a part of the youth camp ministry.”

That powerful experience allowed a kind of compromise between short and long-term missions work, as the teams returned each summer. “It created the opportunity to spend a short time with people overseas in a cultural exchange. Maybe it wasn’t highfalutin evangelism, but there was a way to participate in bringing a gospel message through people who wanted to know more about you as Americans, and we wanted to know about Russia,” he said. “I had to pinch myself every morning that I woke up in a former communist youth camp. I’m actually in Russia.”

As for mission work as a whole, Fullingim sees a wholesale change in the water coming. With less students majoring in the work from the get-go, he envisions more being done by second-career workers, called by the Lord later in life. “After you get a job and you’re working and you have some influence, God calls your heart and stirs that,” he said. “But it does require field training. And if you’re going to go, hey, we’ll train you.”

And even now, after retiring from full-time teaching, Fullingim hopes to aid in that training process. He’ll spend the next phase poring over his journals and the research materials from his time overseas, hoping to resource other missionaries and anthropologists at work in the region. “That’s scientific data, through and through,” he said. “It’s a lot when you’re trying to pile through your archives. But who else can do it?”

So yes—the work continues, even now, as the work always has. The only difference is that Fullingim is allowing himself to take a step back and consider the legacy he leaves behind. “The Lord allowed me to be a part of young people’s lives,” he said. “To learn more about people, to maybe create that interest and excitement in others? It’s been a rewarding career.”

It may not have been what he wanted when he initially signed that first contract in 1987, but the training Fullingim has provided to hundreds of missionaries has proved invaluable to decades of Wesleyan mission work—and to the overall advancement of Christ’s Kingdom in the world.

“The biggest thing that comes to mind about Dr. Mike is his impact on all of Wesleyan missions today,” Alicia reflects. “A large percentage of those serving in Global Partners have been trained by him. His love for exploring other cultures and his emphasis on building trust are playing out in beautifully incarnational ministries around the globe. His impact undoubtedly reaches further than he knows.”