Learned Ladies of the Wesleyan Tradition

Sometimes, the little things are the big things. This is particularly true for women, who for centuries often have fulfilled the Great Commission in quiet but profound ways: the life-giving tenderness of a mother, the soothing encouragement of a wife, the cheers of a sister, or the devotion of a daughter. There is subtle ministry here, and there is vibrant ministry here.

Going “into all the world [to] make disciples” ideally begins at home.

Thinking of the home as the nexus of discipleship is nothing new; in fact, from a historical perspective, it’s a commonplace approach to evangelism. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for example, women bore an extreme amount of responsibility in this regard. So much so, it seems, that educating women was seen as a dangerous undertaking. If women were educated, what might they do? More importantly, what might they neglect?

Thinking of the home as the nexus of discipleship is nothing new; in fact, from a historical perspective, it’s a commonplace approach to evangelism. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for example, women bore an extreme amount of responsibility in this regard. So much so, it seems, that educating women was seen as a dangerous undertaking. If women were educated, what might they do? More importantly, what might they neglect?

In his Sermons to Young Women (1766), James Fordyce, for example, discouraged women from thinking too much. He warned women not to be “metaphysicians, historians, speculative philosophers, or Learned Ladies of any kind.” He was afraid that educated women would “lose in softness what they gained in force; and [should be wary of education] lest the pursuit of such elevation should interfere a little with the plain duties and humble virtues of life.” (Jane Austen fans might remember a reference to Fordyce’s sermons from Pride and Prejudice when the self-absorbed Mr. Collins reads such instruction to the Bennet sisters.)

The historical concern with female learning hits home for those of us concerned with Christian higher education—alumni of a university that has trained countless women for Christian ministry, professional or otherwise. We are hesitant to give voice to modern feminism that persistently reminds us of times past when many religious leaders claimed that for women, learning and virtue are contradictory. But it is important to acknowledge that isolated sermonising does not mark universal, blind cultural acceptance.

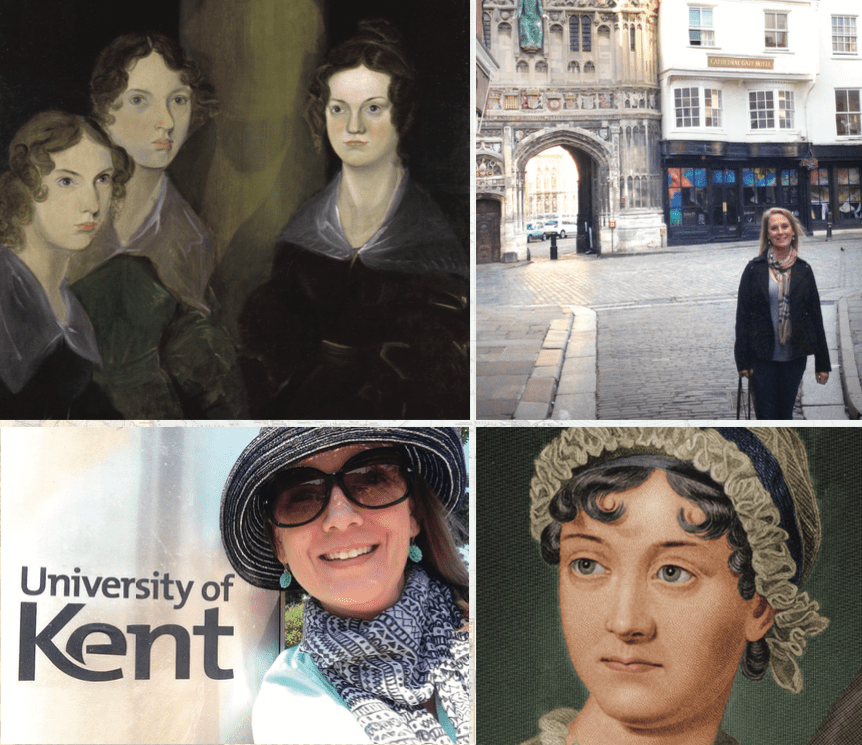

Historically, the Wesleyan tradition has been quite supportive of female learning. Patrick Brontë, the father of the famous Brontë sisters, for example, was an Anglican minister and a follower of John Wesley who saw to it that his daughters were educated both at school and at home. The girls were given full access to his library, a somewhat uncommon privilege. He delighted in their learning. The Brontë sisters’ novels jolted Victorian readership by exposing the corruption of a culture oftentimes steeped in false “manners” when a change of heart was needed.

Wesleyan evangelicalism in England at the turn of the nineteenth century was particularly concerned with full transformation—transformation that begins with the heart. This key message rings true today. A broken world, a world in need of reform, begins within the individual, and change is prompted and performed by the Holy-Spirit. It was just this message that Hannah More, an unmarried Wesleyan evangelical author proclaimed. Her influence championed the evangelical message and profit from her writing funded reform. She was relied upon, listened to, and sought-out. More was actively engaged in the task of making disciples.

The little things, indeed, are the big things. This is true for all of us, men and women alike—and yet today, we often take for granted the extent to which education has transformed the cultural divide between the sexes, at least in the Western world. Women of other nations that neglect female education oftentimes find themselves exploited, suppressed, and abused. Education isn’t the only answer, of course, but it is a start. OKWU’s mission undergirds women to “go into all the world,” whether that be across the globe or right at home. We must be disciples; we must be disciple-makers.